Sometimes I think the process of journalism has changed so much since I started it’s almost unrecognizable. (Scroll down for some early career memories.) But then I consider how much hasn’t changed. Good writing is still good writing, and will be forever. It’s still a craft you can learn, you can always get better at it, and I still love teaching it.

Sometimes I think the process of journalism has changed so much since I started it’s almost unrecognizable. (Scroll down for some early career memories.) But then I consider how much hasn’t changed. Good writing is still good writing, and will be forever. It’s still a craft you can learn, you can always get better at it, and I still love teaching it.

That was just one of the topics I discussed recently with Michael O’Connell, host of the podcast It’s All Journalism, as we looked at NewsLab’s 20-year history, at how storytelling has changed, and what journalists need to know about podcasting. Enjoy, and please forgive the raspy voice–I had a cold that day.

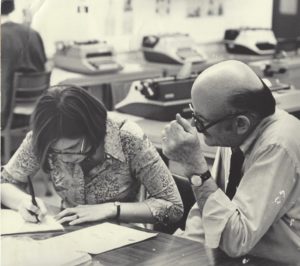

We spent a lot of that conversation looking at today’s journalism challenges, but looking back can be fun, too. Things were so different when I started in journalism you’d almost think it was a different century. Which, of course, it was. How different?

- Manual typewriters. You do know what a typewriter is, right? You put paper in the roller and hope the ribbon has enough ink… oh, never mind. (Yes, electric typewriters existed, but most newsrooms didn’t use them—way too expensive. It was LOUD in newsrooms then).

- Film, not video. Footage got lost in the “soup” or ruined—coming out blue or green–at least once a week. The processor was in a dank space off the newsroom that reeked of chemicals. One of my first jobs was cleaning film with freon, a moderately toxic liquid that left my hands white. I don’t want to think about what I was inhaling. We did have videotape in master control—reels of it two inches wide. To edit, you sliced out a chunk and taped it back together. It wasn’t pretty or precise. Digital was a long way off.

- Cart machines. At KYW in Philadelphia, we rolled audio into our radio newscasts using carts, loops of tape in a plastic case with a cue tone that signaled when to stop. Individual carts ran :30, :40, :60 seconds or longer. When a reporter called in from the field, one of the first questions from master control was, “Will it fit a on a :40?”

- Wire machines. They were loud too, and the multi-ply paper we used was full of nasty chemicals. (Are you noticing a theme here?) When I joined CBS News in 1978, the desk assistants would deliver big rolls of copy to me. If I wasn’t careful it would unroll all over the room. I’d spend the first 20 minutes of each shift ripping the wire copy into story-length chunks using a wooden ruler.

- Smoking. It wasn’t just allowed in newsrooms, it was almost expected. At CBS, I sat across from Dallas Townsend, who went through 3 packs of Lucky Strikes a day. No filter. After more than 30 years at CBS News he ended up being taken off the air when his voice fell apart. Most broadcast journalists I know now don’t smoke. It’s a job killer.

- Dictation. We didn’t have computers or modems, so we called in our scripts for transcription. Sometimes it took so long I thought they had stonecutters in New York engraving the script on a tablet. I got my first “computer” in 1982—a Tandy TRS80, widely known as the TRASH-80, for good reason. It came with a built-in modem: a whopping 300 baud. And I loved it.

- We didn’t have fax machines. Press releases came in the mail. We didn’t have FedEx, either. We didn’t even have beepers in the early days, much less mobile phones. Believe it or not, we had to carry change for pay phones. Of course, a phone call only cost a dime, but you couldn’t be sure you could find a phone when you needed it.

That was then. I’m glad it’s the past. I love the technology we have today. Cell phones, email, tablets, computers, wireless access, and powerful database software, the bottomless research library known as the internet. They’ve simplified our work, and saved us a ton of time. They’ve expanded our reach, as journalists, and given news consumers more choices than anyone could have imagined. And of course they’ve turned that old A.J. Liebling saying about freedom of the press on its head. Freedom of the press may be guaranteed only to those who own one, but the web has made it possible for everyone to own one.

What’s the significance of that? I’ll just suggest one thing. If everyone can be a publisher, then everyone has a stake in protecting the First Amendment. Pass it on.