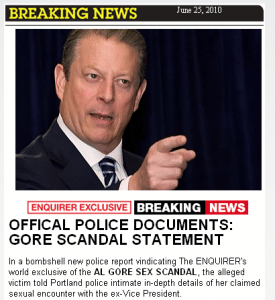

The National Enquirer’s story about what it calls “the Al Gore sex scandal” is a fascinating case study in journalism. Whatever you think about the newsworthiness of an updated police report about an incident that allegedly occurred four years ago and that police refused to investigate, the story behind the story raises plenty of questions.

The National Enquirer’s story about what it calls “the Al Gore sex scandal” is a fascinating case study in journalism. Whatever you think about the newsworthiness of an updated police report about an incident that allegedly occurred four years ago and that police refused to investigate, the story behind the story raises plenty of questions.

The Enquirer says the woman who claims she was sexually assaulted by Gore in 2006 wanted $1 million for her story but was not paid. But if checkbook journalism wasn’t involved, what kind of journalism was?

According to the Washington Post, the tabloid went with the story without even trying to get a reaction from Gore. The Post quotes Enquirer editor John Levine as saying the decision was made “‘for competitive reasons’ out of concern that the former vice president would issue a statement and the paper would lose the exclusive in the two days before it reached newsstands.”

The Enquirer, let’s not forget, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize this year for its reporting of the John Edwards sex scandal. It didn’t win but the paper touted the nomination as evidence of its credibility. There was even talk of “a new era for The Enquirer.” Apparently not.

Fairness is one of the bedrock principles of journalism. You don’t go with a story without checking “the other side.” The public has always suspected that we don’t try very hard to be fair and in some cases they may be right. Leaving a voice-mail after business hours and reporting that someone “could not be reached for comment” doesn’t demonstrate much effort. It reinforces the public’s perception that what matters most to journalists is the “gotcha,” especially if it’s exclusive.

Now, here comes the Enquirer to validate those suspicions with an explicit admission that it was more interested in beating the competition than in due diligence. That may be no surprise to journalists who never thought the tabloid had changed its stripes in the first place. But it also shouldn’t surprise us if more people think that’s the way we all do business. It’s not. And we need to say so.

That’s not the only question worth exploring here. At least one local newspaper in Oregon where the police report was filed knew about it three years ago but never published the story, in part because the woman would not give her name, according to the Washington Post. But the Portland Tribune got a flat denial from Gore’s attorneys in 2007 and 2008 that the allegations were false. Were they too quick to drop the story?

Nobody ever said doing good journalism was easy. There are pressures from all sides–competitive, economic and sometimes political. But journalists should do more than just accept denials when powerful people are involved. And they should definitely not publish allegations–even documented ones–without giving the accused the right to reply.

1 Comment

[…] via No call, no comment | NewsLab. […]