Memo to television networks: Sunlight is the best disinfectant. A little transparency could have saved you from a lot of embarrassment and might have avoided more damage to the already shaky credibility of TV news.

Take the report by ABC’s chief investigative correspondent, Brian Ross, on Toyota’s sudden acceleration problems. The story appeared to disprove the company’s claims that floor mats or driver error were to blame for a rash of high-speed accidents. As Ross was videotaped driving a test car, the engine revved without warning. But what looked like a slam dunk went awry over one two-second close-up.

The money shot of the car’s tachometer surging to 6,000 rpm turned out to have been taken while the car was standing still. The instrument panel lights clearly showed that a brake was on and at least one door was open. ABC insisted the same thing happened during the test drive but the video was blurry, so the crew re-created the effect to get a better image. That may have seemed like a good idea at the time but in the age of YouTube it was incredibly stupid for ABC to think no one would notice.

The money shot of the car’s tachometer surging to 6,000 rpm turned out to have been taken while the car was standing still. The instrument panel lights clearly showed that a brake was on and at least one door was open. ABC insisted the same thing happened during the test drive but the video was blurry, so the crew re-created the effect to get a better image. That may have seemed like a good idea at the time but in the age of YouTube it was incredibly stupid for ABC to think no one would notice.

Justify and disclose

Wasn’t anyone there aware of what can happen when you mess with reality on a news program and fail to disclose it to viewers? Ross should have been. Almost 20 years ago, he worked for “Dateline NBC” when the program aired its infamous General Motors story. The network later admitted it had staged a crash to make it appear that a GM truck’s gas tank had exploded on impact.

Ross was not directly involved in the GM story, and planting an incendiary device and faking one shot are not lapses of the same order of magnitude. But the lesson that should have been learned from one fiasco could have prevented another. It’s pretty simple, really. If you have a good reason for using staged footage, tell the audience exactly what you’ve done and why. If disclosure would taint the story, don’t use it.

The same principle should also apply to people but too often doesn’t. Guests who know their stuff and can express themselves coherently are talk show gold at the networks. They’re experts largely because of their connections. The bookers know this; that’s why they call. But viewers don’t.

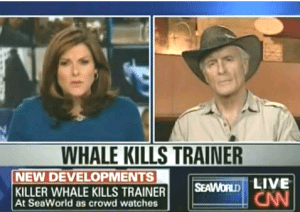

When a whale at SeaWorld in Florida killed a female trainer, CNN and CBS interviewed wildlife expert Jack Hanna, who had nothing but good things to say about the theme park, even though the same whale previously had killed another trainer. “I take my hat off to SeaWorld to take a killer whale that someone said we should euthanize [and] bring it to SeaWorld,” Hanna said on CBS’ “The Early Show.” On CNN, he blamed the death on “human error” and said the whale should not be punished. Neither network bothered to mention that Hanna has a longstanding relationship with SeaWorld, which promotes him on its Web site as “one of our most popular special guests.” Would knowing that have changed viewers’ perceptions of his comments? Undoubtedly.

When a whale at SeaWorld in Florida killed a female trainer, CNN and CBS interviewed wildlife expert Jack Hanna, who had nothing but good things to say about the theme park, even though the same whale previously had killed another trainer. “I take my hat off to SeaWorld to take a killer whale that someone said we should euthanize [and] bring it to SeaWorld,” Hanna said on CBS’ “The Early Show.” On CNN, he blamed the death on “human error” and said the whale should not be punished. Neither network bothered to mention that Hanna has a longstanding relationship with SeaWorld, which promotes him on its Web site as “one of our most popular special guests.” Would knowing that have changed viewers’ perceptions of his comments? Undoubtedly.

Anticipate reactions

And perceptions matter. Many viewers were outraged when the networks aired gruesome video of a luger’s death during a practice run just before the Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Online comments called the decision tasteless and disrespectful, and complained that ratings had trumped ethics.

Was the video news? Absolutely. Were there good journalistic reasons for using it? No question. The footage clearly showed that when the luger lost control, he ran off the track into a steel pillar. In the aftermath of the accident, the track was reshaped and the pillars wrapped in foam. But on the night it happened, viewers were told only that the video was disturbing. “We owe folks a warning here,” NBC News anchor Brian Williams said before running the tape. “These pictures are very tough for some people to watch.”

That kind of disclaimer has been the industry standard for decades, but it serves no useful purpose. Viewers aren’t given enough time to find the remote, much less change channels or turn the TV off, before the video rolls. Instead of washing their hands of the consequences of airing graphic images, newscasters should take responsibility. “We’re showing you this,” the anchor might say, “and here’s why we think it’s important.”

The lack of disclosure at the networks is puzzling, given that many other news organizations have become more open about their editorial decisions. Even the New York Times now puts video of its page-one meetings on the Web. But CBS’ “Public Eye,” a blog whose aim was to bring transparency to the news division, was shut down more than two years ago. NBC’s “Daily Nightly” blog offers glimpses behind the scenes but rarely explains decision-making before the complaints roll in.

It’s time for network newsrooms to pay attention to the late Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. He was right about sunlight being the best disinfectant, and that’s not all. “If we desire respect for the law,” Brandeis said, “we must first make the law respectable.” Same goes for journalism, I’d say.

This column was originally published in American Journalism Review, June/July 2010

2 Comments

Deborah,

I am astounded by the lack of responses to this, even if you did first publish it elsewhere.

So let me say (without intentionally kissing your ass) that it was well-written, and eminently important. You’re talking about ethics and perceptions. Our industry suffers in both those areas. When the big guys make such sloppy mistakes, it makes the rest of us suspect.

Aim high, folks, and scrutinize yourselves as you would your most worrisome rivals.

Agreed that too many newsrooms fail to consider the consequences of their actions, not just on the people they cover and the the people they serve but on their own people, the reputation of their newsroom and by extension on all of journalism. Thanks for weighing in, Wayne.