Cramped and hard to find: That’s my memory of the Freedom Forum’s old Newseum in Rosslyn, Virginia, which closed more than six years ago. Its successor couldn’t be more different: a $435 million palace on prime real estate between the White House and the Capitol in downtown D.C. that finally opens April 11.

Cramped and hard to find: That’s my memory of the Freedom Forum’s old Newseum in Rosslyn, Virginia, which closed more than six years ago. Its successor couldn’t be more different: a $435 million palace on prime real estate between the White House and the Capitol in downtown D.C. that finally opens April 11.

A visit is a busman’s holiday for journalists, but they’re not the main target audience. “Our mission is helping the public understand how important a free press is to a functioning democracy,” says Paul Sparrow, a Newseum vice president. A worthwhile goal, no doubt, but not an easy sell. As we all know, most people don’t have a very good opinion of the news media these days. So why would they bother to pay $20 a head to visit a “museum of news?”

Because it’s entertaining and engaging, Sparrow says, and also because the Newseum puts you face-to-face with history. A gallery dedicated to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, not only displays front-page coverage from papers around the world but also an antenna that fell intact from the top of the World Trade Center. The largest chunks of the Berlin Wall outside Germany are installed so you can walk all the way around them. The west face is covered with garish graffiti. The east face is blank; a 40-foot guard tower looming over it tells why.

Journalists will probably get the biggest kick out of some icons of the industry on display. The original Conus 1 satellite newsgathering truck is so big they had to lower it into place with a crane and construct the building around it. Need a reminder of just how far we’ve come since that hulking truck transformed television news back in 1984? Just check out the Virginia Tech student’s cell phone that captured video and sound during the 2007 shootings there. Then there’s a trunk that belonged to Ed Murrow. It came to the Newseum from a seller whose price included knowing Murrow’s actual first name [hint: It wasn’t Edward].

The back story of some items is more impressive than the objects themselves. The 1976 Datsun in which investigative reporter Don Bolles was killed languished in a Phoenix police impound lot for more than a quarter century. Installed at the Newseum, it’s a reminder of Bolles’ courage and of the unusual collaborative journalism project that picked up where he left off. Bolles, a founding member of Investigative Reporters and Editors, had been covering organized crime for the Arizona Republic when he was killed by a car bomb. His IRE colleagues put competition aside and continued his reporting.

Journalism can be a dangerous business; that’s one message you can’t miss at the Newseum. There’s the body armor ABC’s Bob Woodruff was wearing when he was seriously wounded by a roadside bomb in Iraq in 2006. And there’s a memento of the deadly fighting in Bosnia: the pickup truck that carried Time magazine photographers through a hailstorm of bullets. They made it. But more than 1,600 journalists’ names are listed on a memorial wall dedicated to those killed in the line of duty. Sadly, more will soon be added. (The Committee to Protect Journalists says 65 were killed last year, almost half of them in Iraq.)

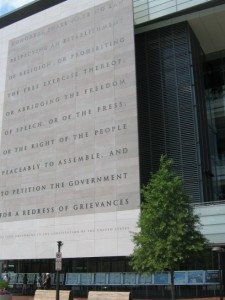

Another message, embodied in the building itself, is a little more subtle: The glass front speaks of openness and transparency. Wall plaques hold quotes that reinforce the importance of the First Amendment and the value of what journalists do. But there are also reminders that journalists don’t always take themselves too seriously. My favorite is from Dave Barry: “TV news can only present the bare bones of a story; it takes a newspaper, with its capability to present vast amounts of information, to render the story truly boring.”

Video plays a big role at the Newseum. There are multiple theaters and kiosks showing “story of news” documentaries, narrated by the likes of ABC’s Charles Gibson, CBS’ Charles Osgood and PBS’ Gwen Ifill. Video interviews with photographers enliven the exhibit of Pulitzer Prize-winning photos.

Kids will like the “4-D” time travel show in the main theater, which combines history with some special sensory effects: water mists, air gusts and shaking seats. Games like “Be a Reporter” also seem aimed at younger visitors. Adults may prefer to compete against the clock and each other in a decision-making game on ethics. Interactive games and role-playing experiences are set up all around the building.

All of this cost big money, and sponsors like News Corp., NBC News and Cox Enterprises paid millions to sponsor galleries. Newseum officials say they don’t see that as a conflict of interest because sponsors had no input on content. “If every other museum in the world can do it, I don’t see why we can’t,” Sparrow says. “We are in places harshly critical” of journalism’s flaws and errors.

If the public gets the point that journalism isn’t easy and that it matters in a free society, the Newseum will have served an important purpose. In the midst of layoffs and buyouts, journalists could stand to be reminded of that as well. When they are, “they get inspired and motivated again,” Sparrow says. “It will reenergize them.”