Twitter got a ton of free publicity this week by releasing #TfN, a newsroom guide for Twitter. “We want to make our tools easier to use so you can focus on your job,” the guide says, “finding sources, verifying facts, publishing stories, promoting your work and yourself—and doing all of it faster and faster all the time.” A laudable goal. But while there are plenty of useful tips in the guide, it’s obviously written for Twitter’s benefit as much as for newsrooms. One example: the only tool recommended for managing multiple streams is Tweetdeck, which Twitter bought last month. There’s no mention of competitors like HootSuite.

Twitter got a ton of free publicity this week by releasing #TfN, a newsroom guide for Twitter. “We want to make our tools easier to use so you can focus on your job,” the guide says, “finding sources, verifying facts, publishing stories, promoting your work and yourself—and doing all of it faster and faster all the time.” A laudable goal. But while there are plenty of useful tips in the guide, it’s obviously written for Twitter’s benefit as much as for newsrooms. One example: the only tool recommended for managing multiple streams is Tweetdeck, which Twitter bought last month. There’s no mention of competitors like HootSuite.

The guide doesn’t go very deep, either. Despite the teaser that the guide will help you verify facts, there’s almost nothing in it about verification. A better source on that comes from from Craig Kanalley of the Huffington Post, creator of Breaking Tweets, who posted this tips on his Twitter Journalism blog in 2009.

So by all means take a look at Twitter’s guide but don’t stop there. Craig Silverman of Regret the Error has an excellent best practices guide for social media verification in CJR. The Knight Digital Media Center published its own Twitter for Journalists guide a week ago that’s also worth a look. It includes links to some newsroom guidelines for using Twitter and other social media. If your newsroom doesn’t have guidelines, I strongly recommend that you consider developing some.

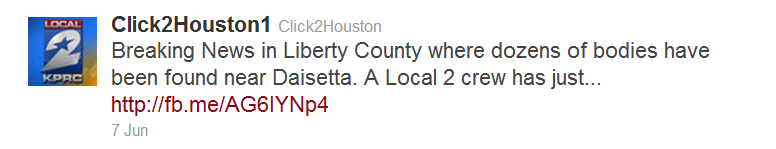

Among other things, you might want to consider how to handle tweets that turn out to be wrong, like this one:

Is it enough to tweet corrected information without mentioning the earlier error? Should erroneous tweets be deleted? Whatever you decide, it’s a good idea to explain your policy and why you chose to go that way.

As for all the tips on verifying information from Twitter, I think it’s most useful to remember some basic questions you’d ask about information from any other source and consider them in a social media context:

1. Who says? Check user bios, websites and blogs to see if they are who they say they are. Look at their associations–who follows them and who they’re following.

2. How do they know this? If locations are enabled on tweets, make sure they’re coming from where they say they are. Check links for details and photos that could establish location.

3. Who else knows this? Look for multiple different sources, not just retweets of the same information or the same information being shared by people who know each other (see #1).

That’s not enough, of course. You have to do your own reporting. If you can’t send a reporter to the scene, use social media to question what you’re reading. Send an @reply or ask your followers to help you. That’s basically how NPR’s Andy Carvin helped to uncover the gay girl in Damascus hoax. The lesson? No matter how many cool tools we have at our disposal, it’s still journalism, folks.